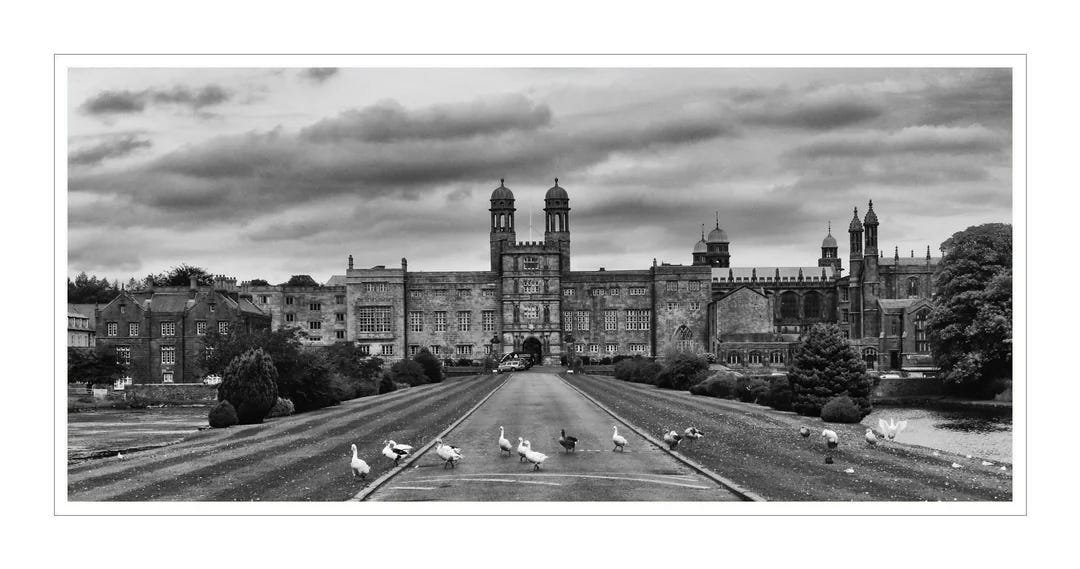

Driving through the folds of Lancashire countryside, Stonyhurst rises like a fortress of learning. Its stone façade, centuries old, has long sheltered a Catholic grammar school, but within its walls lies something more—a museum recently redesigned. My father and I went to see it, curious about its treasures.

The first rooms brim with curiosities: birds preserved with jewel-bright feathers, insects pinned in neat rows, and paintings given by a former students from Peru. They tell the story of a school with global ties, shaped by learning and faith. But we had come for two particular objects that once belonged to monarchs, and which carry within them the pulse of history.

First we viewed the library of many books some detailed different towns and villages within Lancashire as well Henry 8th notes between different parts of his government. To a map drowned up for the wars in Germany. Above the first place was an old metal box that were the fuses for the electric for the lights in the library before this there was gas. Preston and stonyhurst alone with Blackpool were among the first towns to have electric lighting.

A Book of Faith and Blood

Behind glass rests a small prayer book, darkened by time but alive with memory. In the mid-16th century, Queen Mary Tudor—“Bloody Mary” to her Protestant enemies—commissioned a Catholic version of the Book of Common Prayer. She would never read it herself. Death claimed her before its completion, leaving the book to pass instead into the hands of another queen: Mary Stuart of Scotland.

It was this Mary who, in February 1587, mounted the scaffold at Fotheringhay Castle. Accounts tell of her composure, her dignity, and her whispered prayers. It is said that she read her final devotions from this very book, the leather cool in her hands as she prepared to meet her fate. From her it passed to a lady-in-waiting, then to her nephew, then on into the keeping of the Church. Centuries later, without clear reason or fanfare, it found its way to Stonyhurst—perhaps hidden there to keep it safe in a country where Catholic relics often had to live in the shadows.

Looking at it now, the museum is hushed. You feel the weight of two queens bound to its pages: one who dreamed of remaking England Catholic, the other who died with Catholic words on her lips. It is not just parchment and ink; it is a survivor of England’s most turbulent age.

A Coat for a King

Across the gallery stands another relic, no less striking: the coat of Henry VIII. Once, it gleamed on the king’s broad shoulders at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, that dazzling display of rivalry and friendship between England and France. Imagine the scene—tents lined with gold silk, fountains that ran with wine, and two monarchs determined to outshine one another with splendour.

The coat’s design carries echoes of Henry VII, embroidered with Tudor flowers that tie father and son together in thread. To stand before it is to stand before the measure of the man himself. Its size suggests his imposing height and girth; its craftsmanship reflects the wealth and confidence of a monarch who remade church and kingdom alike.

Yet here it rests, still and silent, folded into glass. The same man who once wore it in triumph would later burn through wives, split England from Rome, and die bloated and suspicious. The coat is both a monument to his glory and a shadow of what followed.

Stonyhurst Quiet Power

Taken together, the book and the coat reveal what makes Stonyhurst unique. This is not a grand London institution with endless halls and polished labels. It is a school museum in rural Lancashire, yet it holds treasures that once shaped the destiny of nations.

The Jesuit history of Stonyhurst explains part of this. For centuries, Jesuits collected, preserved, and protected relics of Catholic heritage—sometimes at great risk. In an England that often outlawed their faith, objects like these were hidden, smuggled, or passed carefully from hand to hand. The fact that they now rest here is less an accident than a continuation of that long tradition of guardianship.

Walking those rooms with my father, I felt a quiet awe. Not the awe of grandeur, but the hush of proximity. To see the prayer book is to glimpse Mary Stuart kneeling in her final hour. To see the coat is to imagine Henry VIII striding through a field that glittered like sunlight. These are not distant stories; they are objects you can stand before, their presence almost tangible.

Worth the Journey

For those who find themselves in Lancashire, Stonyhurst is worth the detour. Come for the birds and the paintings, but stay for the moments when history itself seems to breathe from behind glass. In this quiet museum, the lives of queens and kings are not remote tales but realities stitched into silk and inked onto parchment.

At Stonyhurst, history is not merely told. It is preserved, hidden, and revealed again—whispering to those who pause long enough to listen.